Tom Feilden

Tom FeildenBBC.com

Originally posted 22 Feb 17

Here is an excerpt:

The authors should have done it themselves before publication, and all you have to do is read the methods section in the paper and follow the instructions.

Sadly nothing, it seems, could be further from the truth.

After meticulous research involving painstaking attention to detail over several years (the project was launched in 2011), the team was able to confirm only two of the original studies' findings.

Two more proved inconclusive and in the fifth, the team completely failed to replicate the result.

"It's worrying because replication is supposed to be a hallmark of scientific integrity," says Dr Errington.

Concern over the reliability of the results published in scientific literature has been growing for some time.

According to a survey published in the journal Nature last summer, more than 70% of researchers have tried and failed to reproduce another scientist's experiments.

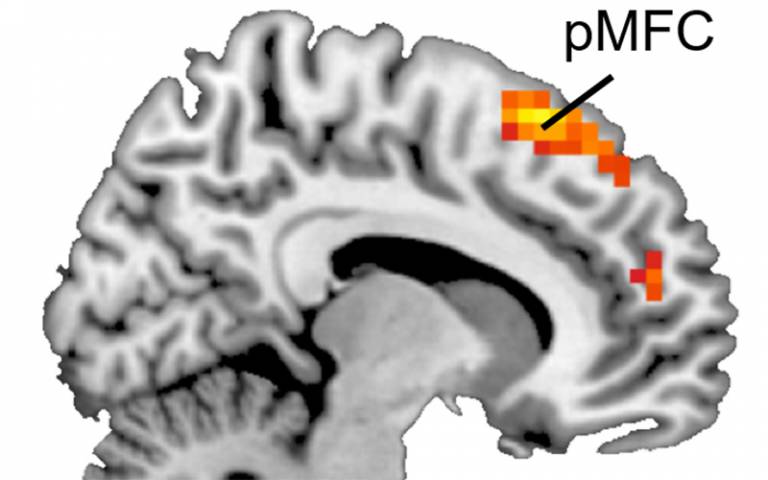

Marcus Munafo is one of them. Now professor of biological psychology at Bristol University, he almost gave up on a career in science when, as a PhD student, he failed to reproduce a textbook study on anxiety.

"I had a crisis of confidence. I thought maybe it's me, maybe I didn't run my study well, maybe I'm not cut out to be a scientist."

The problem, it turned out, was not with Marcus Munafo's science, but with the way the scientific literature had been "tidied up" to present a much clearer, more robust outcome.

The info is here.