Ian Sample

Ian SampleThe Guardian

Originally posted October 20, 2019

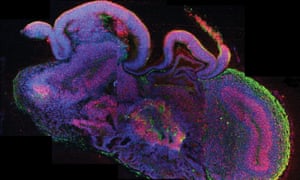

Neuroscientists may have crossed an “ethical rubicon” by growing lumps of human brain in the lab, and in some cases transplanting the tissue into animals, researchers warn.

The creation of mini-brains or brain “organoids” has become one of the hottest fields in modern neuroscience. The blobs of tissue are made from stem cells and, while they are only the size of a pea, some have developed spontaneous brain waves, similar to those seen in premature babies.

Many scientists believe that organoids have the potential to transform medicine by allowing them to probe the living brain like never before. But the work is controversial because it is unclear where it may cross the line into human experimentation.

On Monday, researchers will tell the world’s largest annual meeting of neuroscientists that some scientists working on organoids are “perilously close” to crossing the ethical line, while others may already have done so by creating sentient lumps of brain in the lab.

“If there’s even a possibility of the organoid being sentient, we could be crossing that line,” said Elan Ohayon, the director of the Green Neuroscience Laboratory in San Diego, California. “We don’t want people doing research where there is potential for something to suffer.”

The info is here.