Welcome to the Nexus of Ethics, Psychology, Morality, Philosophy and Health Care

Friday, March 31, 2023

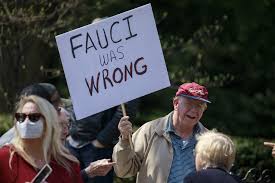

Do conspiracy theorists think too much or too little?

Thursday, March 30, 2023

Institutional Courage Buffers Against Institutional Betrayal, Protects Employee Health, and Fosters Organizational Commitment Following Workplace Sexual Harassment

Wednesday, March 29, 2023

Houston Christian U Sues Tim Clinton & American Assoc of Christian Counselors for Fraud & Breach of Contract

Tuesday, March 28, 2023

Medical assistance in dying (MAiD): Ethical considerations for psychologists

Monday, March 27, 2023

White Supremacist Networks Gab and 8Kun Are Training Their Own AI Now

Sunday, March 26, 2023

State medical board chair Dr. Brian Hyatt resigns, faces Medicaid fraud allegations

Saturday, March 25, 2023

A Christian Health Nonprofit Saddled Thousands With Debt as It Built a Family Empire Including a Pot Farm, a Bank and an Airline

Friday, March 24, 2023

Psychological Features of Extreme Political Ideologies

Thursday, March 23, 2023

Are there really so many moral emotions? Carving morality at its functional joints

Wednesday, March 22, 2023

Young children show negative emotions after failing to help others

Tuesday, March 21, 2023

Mitigating welfare-related prejudice and partisanship among U.S. conservatives with moral reframing of a universal basic income policy

Monday, March 20, 2023

Science through a tribal lens: A group-based account of polarization over scientific facts

Sunday, March 19, 2023

The role of attention in decision-making under risk in gambling disorder: an eye-tracking study

Saturday, March 18, 2023

Black Bioethics in the Age of Black Lives Matter

Friday, March 17, 2023

Rational learners and parochial norms

Thursday, March 16, 2023

Drowning in Debris: A Daughter Faces Her Mother’s Hoarding

Wednesday, March 15, 2023

Why do we focus on trivial things? Bikeshedding explained

Tuesday, March 14, 2023

What Happens When AI Has Read Everything?

Monday, March 13, 2023

Intersectional implicit bias: Evidence for asymmetrically compounding bias and the predominance of target gender

Sunday, March 12, 2023

Growth of AI in mental health raises fears of its ability to run wild

The rise of AI in mental health care has providers and researchers increasingly concerned over whether glitchy algorithms, privacy gaps and other perils could outweigh the technology's promise and lead to dangerous patient outcomes.

Why it matters: As the Pew Research Center recently found, there's widespread skepticism over whether using AI to diagnose and treat conditions will complicate a worsening mental health crisis.

- Mental health apps are also proliferating so quickly that regulators are hard-pressed to keep up.

- The American Psychiatric Association estimates there are more than 10,000 mental health apps circulating on app stores. Nearly all are unapproved.

What's happening: AI-enabled chatbots like Wysa and FDA-approved apps are helping ease a shortage of mental health and substance use counselors.

- The technology is being deployed to analyze patient conversations and sift through text messages to make recommendations based on what we tell doctors.

- It's also predicting opioid addiction risk, detecting mental health disorders like depression and could soon design drugs to treat opioid use disorder.

Driving the news: The fear is now concentrated around whether the technology is beginning to cross a line and make clinical decisions, and what the Food and Drug Administration is doing to prevent safety risks to patients.

- KoKo, a mental health nonprofit, recently used ChatGPT as a mental health counselor for about 4,000 people who weren't aware the answers were generated by AI, sparking criticism from ethicists.

- Other people are turning to ChatGPT as a personal therapist despite warnings from the platform saying it's not intended to be used for treatment.