Denisse Rojas Marquez and Hazel Lever

AMA J Ethics. 2023;25(1):E66-71.

doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2023.66.

Abstract

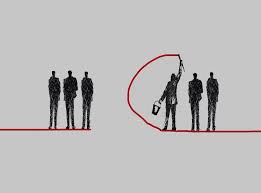

Many health care centers make so-called VIP services available to “very important persons” who have the ability to pay. This article discusses common services (eg, concierge primary care, boutique hotel-style hospital stays) offered to VIPs in health care centers and interrogates “trickle down” economic effects, including the exacerbation of inequity in access to health services and the maldistribution of resources in vulnerable communities. This article also illuminates how VIP care contributes to multitiered health service delivery streams that constitute de facto racial segregation and influence clinicians’ conceptions of what patients deserve from them in health care settings.

Insurance and Influence

It is common practice for health care centers to make “very important person” (VIP) services available to patients because of their status, wealth, or influence. Some delivery models justify the practice of VIP health care as a means to help offset the cost of less profitable sectors of care, which often involve patients who have low income, are uninsured, and are from historically marginalized communities.1 In this article, we explore the justification of VIP health care as helping finance services for patients with low income and consider if this “trickle down” rationale is valid and whether it should be regarded as acceptable. We then discuss clinicians’ ethical responsibilities when taking part in this system of care.

We use the term VIP health care to refer to services that exceed those offered or available to a general patient population through typical health insurance. These services can include concierge primary care (also called boutique or retainer-based medicine) available to those who pay out of pocket, stays on exclusive hospital floors with luxury accommodations, or other premium-level health care services.1 Take the example of a patient who receives treatment on the “VIP floor” of a hospital, where she receives a private room, chef-prepared food, and attending physician-only services. In the outpatient setting, the hallmarks of VIP service are short waiting times, prompt referrals, and round-the-clock staffing.

While this model of “paying for more” is well accepted in other industries, health care is a unique commodity, with different distributional consequences than markets for other goods (eg, accessing it can be a matter of life or death and it is deemed a human right under the Alma-Ata Declaration2). The existence of VIP health care creates several dilemmas: (1) the reinforcement of existing social inequities, particularly racism and classism, through unequal tiers of care; (2) the maldistribution of resources in a resource-limited setting; (3) the fallacy of financing care of the underserved with care of the overserved in a profit-motivated system.

(cut)

Conclusion

VIP health care, while potentially more profitable than traditional health care delivery, has not been shown to produce better health outcomes and may distribute resources away from patients with low incomes and patients of color. A system in which wealthy patients are perceived to be the financial engine for the care of patients with low incomes can fuel distorted ideas of who deserves care, who will provide care, and how expeditiously care will be provided. To allow VIP health care to exist condones the notion that some people—namely, wealthy White people—deserve more care sooner and that their well-being matters more. When health institutions allow VIP care to flourish, they go against the ideal of providing equitable care to all, a value often named in organizational mission statements.22 At a time when pervasive distrust in the medical system has fueled negative consequences for communities of color, it is our responsibility as practitioners to restore and build trust with the most vulnerable in our health care system. When evaluating how VIP care fits into our health care system, we should let health equity be a moral compass for creating a more ethical system.