Knell, S., Rüther, M.

AI Ethics (2023).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00273-w

Abstract

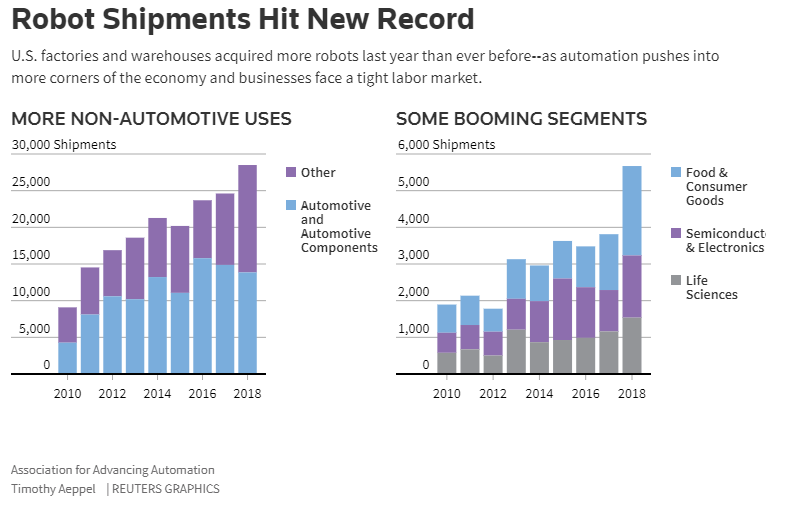

How would it be assessed from an ethical point of view if human wage work were replaced by artificially intelligent systems (AI) in the course of an automation process? An answer to this question has been discussed above all under the aspects of individual well-being and social justice. Although these perspectives are important, in this article, we approach the question from a different perspective: that of leading a meaningful life, as understood in analytical ethics on the basis of the so-called meaning-in-life debate. Our thesis here is that a life without wage work loses specific sources of meaning, but can still be sufficiently meaningful in certain other ways. Our starting point is John Danaher’s claim that ubiquitous automation inevitably leads to an achievement gap. Although we share this diagnosis, we reject his provocative solution according to which game-like virtual realities could be an adequate substitute source of meaning. Subsequently, we outline our own systematic alternative which we regard as a decidedly humanistic perspective. It focuses both on different kinds of social work and on rather passive forms of being related to meaningful contents. Finally, we go into the limits and unresolved points of our argumentation as part of an outlook, but we also try to defend its fundamental persuasiveness against a potential objection.

From Concluding remarks

In this article, we explored the question of how we can find meaning in a post-work world. Our answer relies on a critique of John Danaher’s utopia of games and tries to stick to the humanistic idea, namely to the idea that we do not have to alter our human lifeform in an extensive way and also can keep up our orientation towards common ideals, such as working towards the good, the true and the beautiful.

Our proposal still has some shortcomings, which include the following two that we cannot deal with extensively but at least want to briefly comment on. First, we assumed that certain professional fields, especially in the meaning conferring area of the good, cannot be automated, so that the possibility of mini-jobs in these areas can be considered. This assumption is based on a substantial thesis from the philosophy of mind, namely that AI systems cannot develop consciousness and consequently also no genuine empathy. This assumption needs to be further elaborated, especially in view of some forecasts that even the altruistic and philanthropic professions are not immune to the automation of superefficient systems. Second, we have adopted without further critical discussion the premise of the hybrid standard model of a meaningful life according to which meaning conferring objective value is to be found in the three spheres of the true, the good, and the beautiful. We take this premise to be intuitively appealing, but a further elaboration of our argumentation would have to try to figure out, whether this trias is really exhaustive, and if so, due to which underlying more general principle. Third, the receptive side of finding meaning in the realm of the true and beautiful was emphasized and opposed to the active striving towards meaningful aims. Here, we have to more precisely clarify what axiological status reception has in contrast to active production—whether it is possibly meaning conferring to a comparable extent or whether it is actually just a less meaningful form. This is particularly important to be able to better assess the appeal of our proposal, which depends heavily on the attractiveness of the vita contemplativa.