Halpern SD, Truog RD, and Miller FG.

Halpern SD, Truog RD, and Miller FG.JAMA.

Published online June 29, 2020.

doi:10.1001/jama.2020.11623

Here is an excerpt:

These cognitive errors, which distract leaders from optimal policy making and citizens from taking steps to promote their own and others’ interests, cannot merely be ascribed to repudiations of science. Rather, these biases are pervasive and may have been evolutionarily selected. Even at academic medical centers, where a premium is placed on having science guide policy, COVID-19 action plans prioritized expanding critical care capacity at the outset, and many clinicians treated seriously ill patients with drugs with little evidence of effectiveness, often before these institutions and clinicians enacted strategies to prevent spread of disease.

Identifiable Lives and Optimism Bias

The first error that thwarts effective policy making during crises stems from what economists have called the “identifiable victim effect.” Humans respond more aggressively to threats to identifiable lives, ie, those that an individual can easily imagine being their own or belonging to people they care about (such as family members) or care for (such as a clinician’s patients) than to the hidden, “statistical” deaths reported in accounts of the population-level tolls of the crisis. Similarly, psychologists have described efforts to rescue endangered lives as an inviolable goal, such that immediate efforts to save visible lives cannot be abandoned even if more lives would be saved through alternative responses.

Some may view the focus on saving immediately threatened lives as rational because doing so entails less uncertainty than policies designed to save invisible lives that are not yet imminently threatened. Individuals who harbor such instincts may feel vindicated knowing that during the present pandemic, few if any patients in the US who could have benefited from a ventilator were denied one.

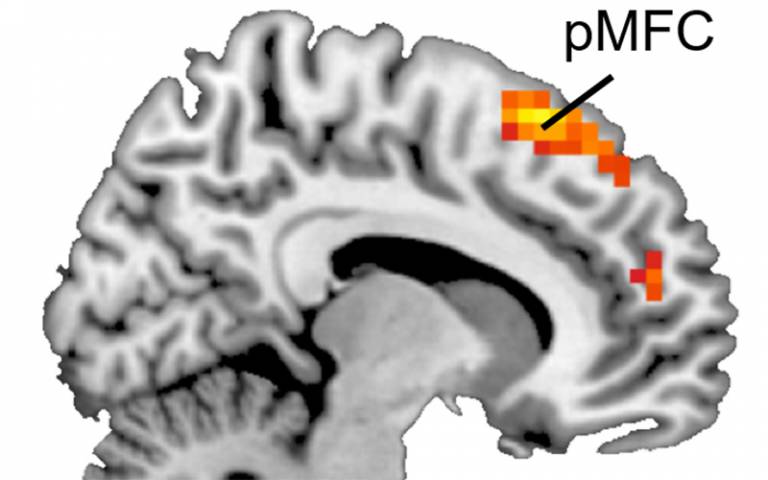

Yet such views represent a second reason for the broad endorsement of policies that prioritize saving visible, immediately jeopardized lives: that humans are imbued with a strong and neurally mediated3 tendency to predict outcomes that are systematically more optimistic than observed outcomes. Early pandemic prediction models provided best-case, worst-case, and most-likely estimates, fully depicting the intrinsic uncertainty.4 Sound policy would have attempted to minimize mortality by doing everything possible to prevent the worst case, but human optimism bias led many to act as if the best case was in fact the most likely.

The info is here.