Owen Flanagan and Gregg D. Caruso

The Philosopher's Magazine

Originally published November 6, 2018

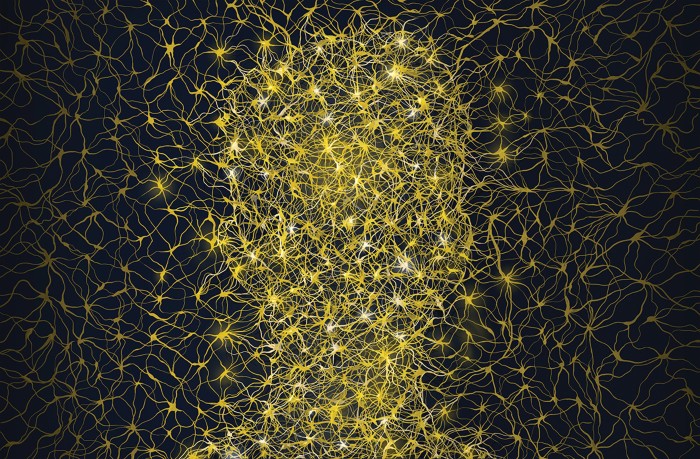

Existentialisms are responses to recognisable diminishments in the self-image of persons caused by social or political rearrangements or ruptures, and they typically involve two steps: (a) admission of the anxiety and an analysis of its causes, and (b) some sort of attempt to regain a positive, less anguished, more hopeful image of persons. With regard to the first step, existentialisms typically involve a philosophical expression of the anxiety that there are no deep, satisfying answers that make sense of the human predicament and explain what makes human life meaningful, and thus that there are no secure foundations for meaning, morals, and purpose. There are three kinds of existentialisms that respond to three different kinds of grounding projects – grounding in God’s nature, in a shared vision of the collective good, or in science. The first-wave existentialism of Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche expressed anxiety about the idea that meaning and morals are made secure because of God’s omniscience and good will. The second-wave existentialism of Sartre, Camus, and de Beauvoir was a post-Holocaust response to the idea that some uplifting secular vision of the common good might serve as a foundation. Today, there is a third-wave existentialism, neuroexistentialism, which expresses the anxiety that, even as science yields the truth about human nature, it also disenchants.

Unlike the previous two waves of existentialism, neuroexistentialism is not caused by a problem with ecclesiastical authority, nor by the shock of coming face to face with the moral horror of nation state actors and their citizens. Rather, neuroexistentialism is caused by the rise of the scientific authority of the human sciences and a resultant clash between the scientific and humanistic image of persons. Neuroexistentialism is a twenty-first-century anxiety over the way contemporary neuroscience helps secure in a particularly vivid way the message of Darwin from 150 years ago: that humans are animals – not half animal, not some percentage animal, not just above the animals, but 100 percent animal. Everyday and in every way, neuroscience removes the last vestiges of an immaterial soul or self. It has no need for such posits. It also suggest that the mind is the brain and all mental processes just are (or are realised in) neural processes, that introspection is a poor instrument for revealing how the mind works, that there is no ghost in the machine or Cartesian theatre where consciousness comes together, that death is the end since when the brain ceases to function so too does consciousness, and that our sense of self may in part be an illusion.

The info is here.

Susan Schneider

Susan Schneider