Gizmodo

Originally published November 30, 2017

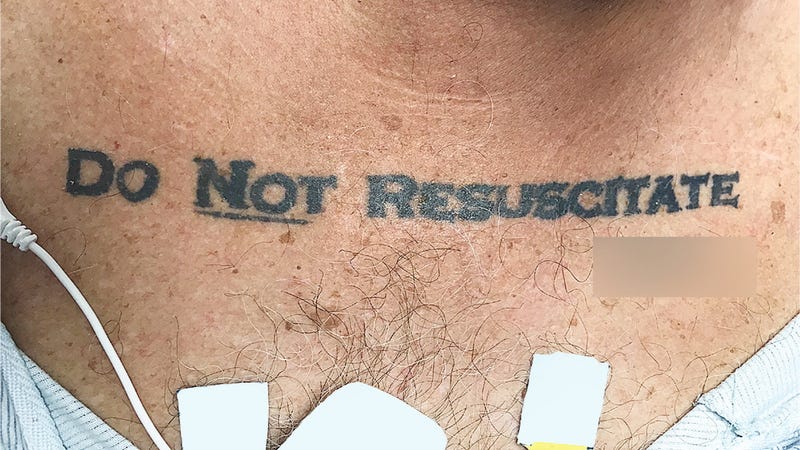

When an unresponsive patient arrived at a Florida hospital ER, the medical staff was taken aback upon discovering the words “DO NOT RESUSCITATE” tattooed onto the man’s chest—with the word “NOT” underlined and with his signature beneath it. Confused and alarmed, the medical staff chose to ignore the apparent DNR request—but not without alerting the hospital’s ethics team, who had a different take on the matter.

When an unresponsive patient arrived at a Florida hospital ER, the medical staff was taken aback upon discovering the words “DO NOT RESUSCITATE” tattooed onto the man’s chest—with the word “NOT” underlined and with his signature beneath it. Confused and alarmed, the medical staff chose to ignore the apparent DNR request—but not without alerting the hospital’s ethics team, who had a different take on the matter.But with the “DO NOT RESUSCITATE” tattoo glaring back at them, the ICU team was suddenly confronted with a serious dilemma. The patient arrived at the hospital without ID, the medical staff was unable to contact next of kin, and efforts to revive or communicate with the patient were futile. The medical staff had no way of knowing if the tattoo was representative of the man’s true end-of-life wishes, so they decided to play it safe and ignore it.

The article is here.