Welcome to the Nexus of Ethics, Psychology, Morality, Philosophy and Health Care

Sunday, June 18, 2023

Gender-Affirming Care for Trans Youth Is Neither New nor Experimental: A Timeline and Compilation of Studies

Saturday, June 17, 2023

Debt Collectors Want To Use AI Chatbots To Hustle People For Money

Friday, June 16, 2023

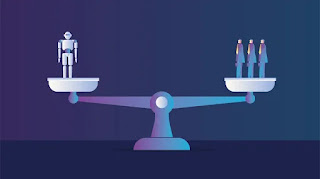

ChatGPT Is a Plagiarism Machine

Thursday, June 15, 2023

Moralization and extremism robustly amplify myside sharing

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

Can Robotic AI Systems Be Virtuous and Why Does This Matter?

Tuesday, June 13, 2023

Using the Veil of Ignorance to align AI systems with principles of justice

Monday, June 12, 2023

Why some mental health professionals avoid self-care

Sunday, June 11, 2023

Podcast: Ethics Education and the Impact of AI on Mental Health

Baxter, R. (2023, June 8). Lawyer’s AI Blunder Shows Perils of ChatGPT in ‘Early Days.’ Bloomberg Law News. Retrieved from https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and-practice/lawyers-ai-blunder-shows-perils-of-chatgpt-in-early-days

Chen, J., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhang, X., & Li, J. (2023). Deep learning-guided discovery of an antibiotic targeting Acinetobacter baumannii. Nature Biotechnology, 31(6), 631-636. doi:10.1038/s41587-023-00949-7

Dillon, D, Tandon, N., Gu, Y., & Gray, K. (2023). Can AI language models replace human participants? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, in press.

Fowler, A. (2023, June 7). Artificial intelligence could help predict breast cancer risk. USA Today. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/06/07/artificial-intelligence-breast-cancer-risk-prediction/70297531007/

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Handelsman, M. M., Gottlieb, M. C., & Knapp, S. (2005). Training ethical psychologists: An acculturation model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.1.59

Heinlein, R. A. (1961). Stranger in a strange land. New York, NY: Putnam.

Knapp, S. J., & VandeCreek, L. D. (2006). Practical ethics for psychologists: A positive approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

MacIver M. B. (2022). Consciousness and inward electromagnetic field interactions. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 16, 1032339. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.1032339

Persson, G., Restori, K. H., Emdrup, J. H., Schussek, S., Klausen, M. S., Nicol, M. J., Katkere, B., Rønø, B., Kirimanjeswara, G., & Sørensen, A. B. (2023). DNA immunization with in silico predicted T-cell epitopes protects against lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18-hACE2 mice. Frontiers in Immunology, 14, 1166546. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1166546

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universalism-particularism: Values in the context of cultural evolution. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1-65). New York, NY: Academic Press.