Amormino, P., Ploe, M.L. & Marsh, A.A.

Sci Rep 12, 22111 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26418-1

Abstract

Donating a kidney to a stranger is a rare act of extraordinary altruism that appears to reflect a moral commitment to helping others. Yet little is known about patterns of moral cognition associated with extraordinary altruism. In this preregistered study, we compared the moral foundations, values, and patterns of utilitarian moral judgments in altruistic kidney donors (n = 61) and demographically matched controls (n = 58). Altruists expressed more concern only about the moral foundation of harm, but no other moral foundations. Consistent with this, altruists endorsed utilitarian concerns related to impartial beneficence, but not instrumental harm. Contrary to our predictions, we did not find group differences between altruists and controls in basic values. Extraordinary altruism generally reflected opposite patterns of moral cognition as those seen in individuals with psychopathy, a personality construct characterized by callousness and insensitivity to harm and suffering. Results link real-world, costly, impartial altruism primarily to moral cognitions related to alleviating harm and suffering in others rather than to basic values, fairness concerns, or strict utilitarian decision-making.

Discussion

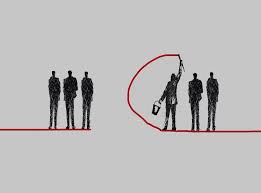

In the first exploration of patterns of moral cognition that characterize individuals who have engaged in real-world extraordinary altruism, we found that extraordinary altruists are distinguished from other people only with respect to a narrow set of moral concerns: they are more concerned with the moral foundation of harm/care, and they more strongly endorse impartial beneficence. Together, these findings support the conclusion that extraordinary altruists are morally motivated by an impartial concern for relieving suffering, and in turn, are motivated to improve others’ welfare in a self-sacrificial manner that does not allow for the harm of others in the process. These results are also partially consistent with extraordinary altruism representing the inverse of psychopathy in terms of moral cognition: altruists score lower in psychopathy (with the strongest relationships observed for psychopathy subscales associated with socio-affective responding) and higher-psychopathy participants most reliably endorse harm/care less than lower psychopathy participants, with participants with higher scores on the socio-affective subscales of our psychopathy measures also endorsing impartial beneficence less strongly.

(cut)

Notably, and contrary to our predictions, we did not find that donating a kidney to a stranger is strongly or consistently correlated (positively or negatively) with basic values like universalism, benevolence, power, hedonism, or conformity. That suggests extraordinary altruism may not be driven by unusual values, at least as they are measured by the Schwartz inventory, but rather by specific moral concerns (such as harm/care). Our findings suggest that reported values may not in themselves predict whether one acts on those values when it comes to extraordinary altruism, much as “…a person can value being outgoing in social gatherings, independently of whether they are prone to acting in a lively or sociable manner”. Similarly, people who share a common culture may value common things but acting on those values to an extraordinarily costly and altruistic degree may require a stronger motivation––a moral motivation.