Carolyn Y. Johnson

www.iol.za

Originally posted September 3, 2018

Here is an excerpt:

Five years ago, an ethical debate about organoids seemed to many scientists to be premature. The organoids were exciting because they were similar to the developing brain, and yet they were incredibly rudimentary. They were constrained in how big they could get before cells in the core started dying, because they weren't suffused with blood vessels or supplied with nutrients and oxygen by a beating heart. They lacked key cell types.

Still, there was something different about brain organoids compared with routine biomedical research. Song recalled that one of the amazing but also unsettling things about the early organoids was that they weren't as targeted to develop into specific regions of the brain, so it was possible to accidentally get retinal cells.

"It's difficult to see the eye in a dish," Song said.

Now, researchers are succeeding at keeping organoids alive for longer periods of time. At a talk, Hyun recalled one researcher joking that the lab had sung "Happy Birthday" to an organoid when it was a year old. Some researchers are implanting organoids into rodent brains, where they can stay alive longer and grow more mature. Others are building multiple organoids representing different parts of the brain, such as the hippocampus, which is involved in memory, or the cerebral cortex - the seat of cognition - and fusing them together into larger "assembloids."

Even as scientists express scepticism that brain organoids will ever come close to sentience, they're the ones calling for a broad discussion, and perhaps more oversight. The questions range from the practical to the fantastical. Should researchers make sure that people who donate their cells for organoid research are informed that they could be used to make a tiny replica of parts of their brain? If organoids became sophisticated enough, should they be granted greater protections, like the rules that govern animal research? Without a consensus on what consciousness or pain would even look like in the brain, how will scientists know when they're nearing the limit?

The info is here.

Welcome to the Nexus of Ethics, Psychology, Morality, Philosophy and Health Care

Welcome to the nexus of ethics, psychology, morality, technology, health care, and philosophy

Thursday, September 20, 2018

John Rawls’ ‘A Theory of Justice’

Ben Davis

1000-Word Philosophy

Originally posted July 27, 2018

Here is an excerpt:

Reasonable people often disagree about how to live, but we need to structure society in a way that reasonable members of that society can accept. Citizens could try to collectively agree on basic rules. We needn’t decide every detail: we might only worry about rules concerning major political and social institutions, like the legal system and economy, which form the ‘basic structure’ of society.

A collective agreement on the basic structure of society is an attractive ideal. But some people are more powerful than others: some may be wealthier, or part of a social majority. If people can dominate negotiations because of qualities that are, as Rawls (72-75) puts it, morally arbitrary, that is wrong. People don’t earn these advantages: they get them by luck. For anyone to use these unearned advantages to their own benefit is unfair, and the source of many injustices.

This inspires Rawls’ central claim that we should conceive of justice ‘as fairness.’ To identify fairness, Rawls (120) develops two important concepts: the original position and the veil of ignorance:

The original position is a hypothetical situation: Rawls asks what social rules and institutions people would agree to, not in an actual discussion, but under fair conditions, where nobody knows whether they are advantaged by luck. Fairness is achieved through the veil of ignorance, an imagined device where the people choosing the basic structure of society (‘deliberators’) have morally arbitrary features hidden from them: since they have no knowledge of these features, any decision they make can’t be biased in their own favour.

The brief, excellent synopsis is here.

1000-Word Philosophy

Originally posted July 27, 2018

Here is an excerpt:

Reasonable people often disagree about how to live, but we need to structure society in a way that reasonable members of that society can accept. Citizens could try to collectively agree on basic rules. We needn’t decide every detail: we might only worry about rules concerning major political and social institutions, like the legal system and economy, which form the ‘basic structure’ of society.

A collective agreement on the basic structure of society is an attractive ideal. But some people are more powerful than others: some may be wealthier, or part of a social majority. If people can dominate negotiations because of qualities that are, as Rawls (72-75) puts it, morally arbitrary, that is wrong. People don’t earn these advantages: they get them by luck. For anyone to use these unearned advantages to their own benefit is unfair, and the source of many injustices.

This inspires Rawls’ central claim that we should conceive of justice ‘as fairness.’ To identify fairness, Rawls (120) develops two important concepts: the original position and the veil of ignorance:

The original position is a hypothetical situation: Rawls asks what social rules and institutions people would agree to, not in an actual discussion, but under fair conditions, where nobody knows whether they are advantaged by luck. Fairness is achieved through the veil of ignorance, an imagined device where the people choosing the basic structure of society (‘deliberators’) have morally arbitrary features hidden from them: since they have no knowledge of these features, any decision they make can’t be biased in their own favour.

The brief, excellent synopsis is here.

Wednesday, September 19, 2018

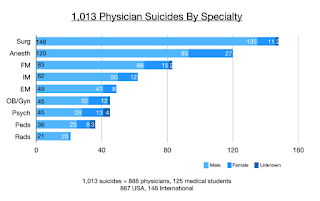

Why “happy” doctors die by suicide

Pamela Wible

Pamela Wiblewww.idealmedicalcare.org

Originally posted on August 24, 2018

Here is an excerpt:

Doctor suicides on the registry were submitted to me during a six-year period (2012-2018) by families, friends, and colleagues who knew the deceased. After speaking to thousands of suicidal physicians since 2012 on my informal doctor suicide hotline and analyzing registry data, I discovered surprising themes—many unique to physicians.

Public perception maintains that doctors are successful, intelligent, wealthy, and immune from the problems of the masses. To patients, it is inconceivable that doctors would have the highest suicide rate of any profession (5).

Even more baffling, “happy” doctors are dying by suicide. Many doctors who kill themselves appear to be the most optimistic, upbeat, and confident people. Just back from Disneyland, just bought tickets for a family cruise, just gave a thumbs up to the team after a successful surgery—and hours later they shoot themselves in the head.

Doctors are masters of disguise and compartmentalization.

Turns out some of the happiest people—especially those who spend their days making other people happy—may be masking their own despair.

The info is here.

Many Cultures, One Psychology?

Nicolas Geeraert

American Scientist

Originally published in the July-August issue

Here is an excerpt:

The Self

If you were asked to describe yourself, what would you say? Would you list your personal characteristics, such as being intelligent or funny, or would you use preferences, such as “I love pizza”? Or perhaps you would instead mention social relationships, such as “I am a parent”? Social psychologists have long maintained that people are much more likely to describe themselves and others in terms of stable personal characteristics than they are to describe themselves in terms of their preferences or relationships.

However, the way people describe themselves seems to be culturally bound. In a landmark 1991 paper, social psychologists Hazel R. Markus and Shinobu Kitayama put forward the idea that self-construal is culturally variant, noting that individuals in some cultures understand the self as independent, whereas those in other cultures perceive it as interdependent.

People with an independent self-construal view themselves as free, autonomous, and unique individuals, possessing stable boundaries and a set of fixed characteristics or attributes by which their actions are guided. Independent self-construal is more prevalent in Europe and North America. By contrast, people with an interdependent self-construal see themselves as more connected with others close to them, such as their family or community, and think of themselves as a part of different social relationships.

The information is here.

American Scientist

Originally published in the July-August issue

Here is an excerpt:

The Self

If you were asked to describe yourself, what would you say? Would you list your personal characteristics, such as being intelligent or funny, or would you use preferences, such as “I love pizza”? Or perhaps you would instead mention social relationships, such as “I am a parent”? Social psychologists have long maintained that people are much more likely to describe themselves and others in terms of stable personal characteristics than they are to describe themselves in terms of their preferences or relationships.

However, the way people describe themselves seems to be culturally bound. In a landmark 1991 paper, social psychologists Hazel R. Markus and Shinobu Kitayama put forward the idea that self-construal is culturally variant, noting that individuals in some cultures understand the self as independent, whereas those in other cultures perceive it as interdependent.

People with an independent self-construal view themselves as free, autonomous, and unique individuals, possessing stable boundaries and a set of fixed characteristics or attributes by which their actions are guided. Independent self-construal is more prevalent in Europe and North America. By contrast, people with an interdependent self-construal see themselves as more connected with others close to them, such as their family or community, and think of themselves as a part of different social relationships.

The information is here.

Tuesday, September 18, 2018

Changing the way we communicate about patients

Abraar Karan

BMJ Blog

Originally posted August 29, 2018

Here is an excerpt:

There are many changes that we can make to improve how we communicate about patients. One of the easiest and most critical transformations is how we write our medical notes. One of the best doctors I ever worked with did exactly this, and is famous at the Brigham (our hospital) for doing it. He systematically starts every single note with the person’s social history. Who is this patient? It is not just a lady with abdominal pain. It is a mother of three, a retired teacher, and an active cyclist. That is the first thing we read about her, and so when I enter her room, I can’t help but see her this way rather than as a case of appendicitis.

This matters because patients deserve to be treated as people—a statement that’s so obvious it shouldn’t need to be said, but which physician behaviour doesn’t always reflect. You wouldn’t expect to know the most sensitive and vulnerable aspects of someone before even knowing their most basic background, yet we do this in medicine all the time. This is also important because in many clinical presentations, it provides critical information that helps deduce how they got sick, and why they may get sick again in the same way if we don’t restructure something essential in their life. For instance, if I didn’t know that the 22 year old opioid addict had just been kicked out of his house and is on the street without transportation to get to his suboxone clinic, I will not have truly solved what brought him to the hospital in the first place.

The info is here.

BMJ Blog

Originally posted August 29, 2018

Here is an excerpt:

There are many changes that we can make to improve how we communicate about patients. One of the easiest and most critical transformations is how we write our medical notes. One of the best doctors I ever worked with did exactly this, and is famous at the Brigham (our hospital) for doing it. He systematically starts every single note with the person’s social history. Who is this patient? It is not just a lady with abdominal pain. It is a mother of three, a retired teacher, and an active cyclist. That is the first thing we read about her, and so when I enter her room, I can’t help but see her this way rather than as a case of appendicitis.

This matters because patients deserve to be treated as people—a statement that’s so obvious it shouldn’t need to be said, but which physician behaviour doesn’t always reflect. You wouldn’t expect to know the most sensitive and vulnerable aspects of someone before even knowing their most basic background, yet we do this in medicine all the time. This is also important because in many clinical presentations, it provides critical information that helps deduce how they got sick, and why they may get sick again in the same way if we don’t restructure something essential in their life. For instance, if I didn’t know that the 22 year old opioid addict had just been kicked out of his house and is on the street without transportation to get to his suboxone clinic, I will not have truly solved what brought him to the hospital in the first place.

The info is here.

The So-Called Right to Try Law Gives Patients False Hope

Claudia Wallis

Scientific American

Originally posted in the September 2018 issue

There's no question about it: the new law sounds just great. President Donald Trump, who knows a thing or two about marketing, gushed about its name when he signed the “Right to Try” bill into law on May 30. He was surrounded by patients with incurable diseases, including a second grader with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, who got up from his small wheelchair to hug the president. The law aims to give such patients easier access to experimental drugs by bypassing the Food and Drug Administration.

The crowd-pleasing name and concept are why 40 states had already passed similar laws, although they were largely symbolic until the federal government got onboard. The laws vary but generally say that dying patients may seek from drugmakers any medicine that has passed a phase I trial—a minimal test of safety. “We're going to be saving tremendous numbers of lives,” Trump said. “The current FDA approval process can take many, many years. For countless patients, time is not what they have.”

But the new law won't do what the president claims. Instead it gives false hope to the most vulnerable patients. “This is a right to ask, not a right to try,” says Alison Bateman-House, a medical ethicist at New York University and an expert on the compassionate use of experimental drugs.

The info is here.

Scientific American

Originally posted in the September 2018 issue

There's no question about it: the new law sounds just great. President Donald Trump, who knows a thing or two about marketing, gushed about its name when he signed the “Right to Try” bill into law on May 30. He was surrounded by patients with incurable diseases, including a second grader with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, who got up from his small wheelchair to hug the president. The law aims to give such patients easier access to experimental drugs by bypassing the Food and Drug Administration.

The crowd-pleasing name and concept are why 40 states had already passed similar laws, although they were largely symbolic until the federal government got onboard. The laws vary but generally say that dying patients may seek from drugmakers any medicine that has passed a phase I trial—a minimal test of safety. “We're going to be saving tremendous numbers of lives,” Trump said. “The current FDA approval process can take many, many years. For countless patients, time is not what they have.”

But the new law won't do what the president claims. Instead it gives false hope to the most vulnerable patients. “This is a right to ask, not a right to try,” says Alison Bateman-House, a medical ethicist at New York University and an expert on the compassionate use of experimental drugs.

The info is here.

Monday, September 17, 2018

Who Is Experiencing What Kind of Moral Distress?

Carina Fourie

AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(6):578-584.

Abstract

Moral distress, according to Andrew Jameton’s highly influential definition, occurs when a nurse knows the morally correct action to take but is constrained in some way from taking this action. The definition of moral distress has been broadened, first, to include morally challenging situations that give rise to distress but which are not necessarily linked to nurses feeling constrained, such as those associated with moral uncertainty. Second, moral distress has been broadened so that it is not confined to the experiences of nurses. However, such a broadening of the concept does not mean that the kind of moral distress being experienced, or the role of the person experiencing it, is morally irrelevant. I argue that differentiating between categories of distress—e.g., constraint and uncertainty—and between groups of health professionals who might experience moral distress is potentially morally relevant and should influence the analysis, measurement, and amelioration of moral distress in the clinic.

The info is here.

AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(6):578-584.

Abstract

Moral distress, according to Andrew Jameton’s highly influential definition, occurs when a nurse knows the morally correct action to take but is constrained in some way from taking this action. The definition of moral distress has been broadened, first, to include morally challenging situations that give rise to distress but which are not necessarily linked to nurses feeling constrained, such as those associated with moral uncertainty. Second, moral distress has been broadened so that it is not confined to the experiences of nurses. However, such a broadening of the concept does not mean that the kind of moral distress being experienced, or the role of the person experiencing it, is morally irrelevant. I argue that differentiating between categories of distress—e.g., constraint and uncertainty—and between groups of health professionals who might experience moral distress is potentially morally relevant and should influence the analysis, measurement, and amelioration of moral distress in the clinic.

The info is here.

How our lives end must no longer be a taboo subject

Kathryn Mannix

The Guardian

Originally published August 16, 2018

Here is an excerpt:

As we age and develop long-term health conditions, our chances of becoming suddenly ill rise; prospects for successful resuscitation fall; our youthful assumptions about length of life may be challenged; and our quality of life becomes increasingly more important to us than its length. The number of people over the age of 85 will double in the next 25 years, and dementia is already the biggest cause of death in this age group. What discussions do we need to have, and to repeat at sensible intervals, to ensure that our values and preferences are understood by the people who may be asked about them?

Our families need to know our answers to such questions as: how much treatment is too much or not enough? Do we see artificial hydration and nutrition as “treatment” or as basic care? Is life at any cost or quality of life more important to us? And what gives us quality of life? A 30-year-old attorney may not understand that being able to hear birdsong, or enjoy ice-cream, or follow the racing results, is more important to a family’s 85-year-old relative than being able to walk or shop. When we are approaching death, what important things should our carers know about us?

The info is here.

The Guardian

Originally published August 16, 2018

Here is an excerpt:

As we age and develop long-term health conditions, our chances of becoming suddenly ill rise; prospects for successful resuscitation fall; our youthful assumptions about length of life may be challenged; and our quality of life becomes increasingly more important to us than its length. The number of people over the age of 85 will double in the next 25 years, and dementia is already the biggest cause of death in this age group. What discussions do we need to have, and to repeat at sensible intervals, to ensure that our values and preferences are understood by the people who may be asked about them?

Our families need to know our answers to such questions as: how much treatment is too much or not enough? Do we see artificial hydration and nutrition as “treatment” or as basic care? Is life at any cost or quality of life more important to us? And what gives us quality of life? A 30-year-old attorney may not understand that being able to hear birdsong, or enjoy ice-cream, or follow the racing results, is more important to a family’s 85-year-old relative than being able to walk or shop. When we are approaching death, what important things should our carers know about us?

The info is here.

Sunday, September 16, 2018

Time to abandon grand ethical theories?

Julian Baggini

TheTLS.co

Originally posted May 22, 2018

Here are two excerpts:

Social psychologists, sociologists and anthropologists would not be baffled by this apparent contradiction. Many have long believed that morality is essentially a system of social regulation. As such it is in no more need of a divine foundation or a philosophical justification than folk dancing or tribal loyalty. Indeed, if ethics is just the management of the social sphere, it should not be surprising that as we live in a more globalized world, ethics becomes enlarged to encompass not only how we treat kith and kin but our distant neighbours too.

Philosophers have more to worry about. They are not generally satisfied to see morality as a purely pragmatic means of keeping the peace. To see the world muddling through morality is deeply troubling. Where’s the consistency? Where’s the theoretical framework? Where’s the argument?

(cut)

There is then a curious combination of incoherence and vagueness about just what it is to be ethical, and a bogus precision in the ways in which organizations prove themselves to be good. All this confusion helps fuel philosophical ethics, which has become a vibrant, thriving discipline, providing academic presses with a steady stream of books. Looking over a sample of their recent output, it is evident that moral philosophers are keen to show that they are not just playing intellectual games and that they have something to offer the world.

The info is here.

TheTLS.co

Originally posted May 22, 2018

Here are two excerpts:

Social psychologists, sociologists and anthropologists would not be baffled by this apparent contradiction. Many have long believed that morality is essentially a system of social regulation. As such it is in no more need of a divine foundation or a philosophical justification than folk dancing or tribal loyalty. Indeed, if ethics is just the management of the social sphere, it should not be surprising that as we live in a more globalized world, ethics becomes enlarged to encompass not only how we treat kith and kin but our distant neighbours too.

Philosophers have more to worry about. They are not generally satisfied to see morality as a purely pragmatic means of keeping the peace. To see the world muddling through morality is deeply troubling. Where’s the consistency? Where’s the theoretical framework? Where’s the argument?

(cut)

There is then a curious combination of incoherence and vagueness about just what it is to be ethical, and a bogus precision in the ways in which organizations prove themselves to be good. All this confusion helps fuel philosophical ethics, which has become a vibrant, thriving discipline, providing academic presses with a steady stream of books. Looking over a sample of their recent output, it is evident that moral philosophers are keen to show that they are not just playing intellectual games and that they have something to offer the world.

The info is here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)