Chandrashekar, S., et al. (2025, May 26).

PsyArXiv Preprints

Abstract

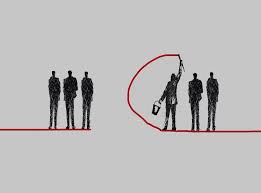

Trust plays a central role in social interactions. Recent research has highlighted the importance of others’ moral decisions in shaping trust inference: individuals who reject sacrificial harm in moral dilemmas (which aligns with deontological ethics) are generally perceived as more trustworthy than those who condone sacrificial harm (which aligns with utilitarian ethics). Across five studies (N = 1234), we investigated trust inferences in the context of iterative moral dilemmas, which allow individuals to not only make deontological or utilitarian decisions, but also harm-balancing decisions. Our findings challenge the prevailing perspective: While we did observe effects of the type of moral decision that people make, the direction of these effects was inconsistent across studies. In contrast, moral similarity (i.e., whether a decision aligns with one’s own perspective) consistently predicted increased trust. Our findings suggest that trust is not just about adhering to specific moral frameworks but also about shared moral perspectives.

Here are some thoughts:

This research is important to practicing psychologists for several key reasons. It demonstrates that like-mindedness —specifically, sharing similar moral judgments or decision-making patterns—is a strong determinant of perceived trustworthiness. This insight is valuable across clinical, organizational, and social psychology, particularly in understanding how moral alignment influences interpersonal relationships.

Unlike past studies focused on isolated moral dilemmas like the trolley problem, this work explores iterative dilemmas, offering a more realistic model of how people make repeated moral decisions over time. For psychologists working in ethics or behavioral interventions, this provides a nuanced framework for promoting cooperation and ethical behavior in dynamic contexts.

The study also challenges traditional views by showing that individuals who switch between utilitarian and deontological reasoning are not necessarily seen as less trustworthy, suggesting flexibility in moral judgment may be contextually appropriate. Additionally, the research highlights how moral decisions shape perceptions of traits such as bravery, warmth, and competence—key factors in how people are judged socially and professionally.

These findings can aid therapists in helping clients navigate relational issues rooted in moral misalignment or trust difficulties. Overall, the research bridges moral psychology and social perception, offering practical tools for improving interpersonal trust across diverse psychological domains.