Jessica Davis

Jessica DavisJustSecurity.org

Originally posted 31 March 20

Here is an excerpt:

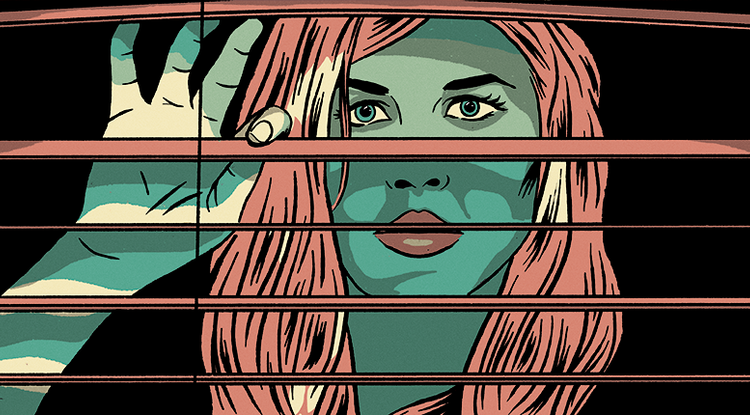

It is imperative that States and their citizens question how much freedom and privacy should be sacrificed to limit the impact of this pandemic. It is also not sufficient to ask simply “if” something is legal; we should also ask whether it should be, and under what circumstances. States should consider the ethics of surveillance and intelligence, specifically whether it is justified, done under the right authority, if it can be done with intentionality and proportionality and as a last resort, and if targets of surveillance can be separated from non-targets to avoid mass surveillance. These considerations, combined with enhanced transparency and sunset clauses on the use of intelligence and surveillance techniques, can allow States to ethically deploy these powerful tools to help stop the spread of the virus.

States are employing intelligence and surveillance techniques to contain the spread of the illness because these methods can help track and identify infected or exposed people and enforce quarantines. States have used cell phone data to track people at risk of infection or transmission and financial data to identify places frequented by at-risk people. Social media intelligence is also ripe for exploitation in terms of identifying social contacts. This intelligence, is increasingly being combined with health data, creating a unique (and informative) picture of a person’s life that is undoubtedly useful for virus containment. But how long should States have access to this type of information on their citizens, if at all? Considering natural limits to the collection of granular data on citizens is imperative, both in terms of time and access to this data.

The info is here.