Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

123(4), 676–692.

https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000303

Abstract

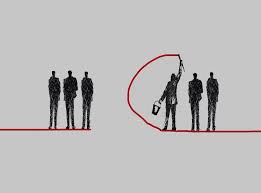

The widespread demand for luxury is best understood by the social advantages of signaling status (i.e., conspicuous consumption; Veblen, 1899). In the present research, we examine the limits of this perspective by studying the implications of status signaling for cooperation. Cooperation is principally about caring for others, which is fundamentally at odds with the self-promotional nature of signaling status. Across behaviorally consequential Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) games and naturalistic scenario studies, we investigate both sides of the relationship between signaling and cooperation: (a) how people respond to others who signal status, as well as (b) the strategic choices people make about whether to signal status. In each case, we find that people recognize the relative advantage of modesty (i.e., the inverse of signaling status) and behave strategically to enable cooperation. That is, people are less likely to cooperate with partners who signal status compared to those who are modest (Studies 1 and 2), and more likely to select a modest person when cooperation is desirable (Study 3). These behaviors are consistent with inferences that status signalers are less prosocial and less prone to cooperate. Importantly, people also refrain from signaling status themselves when it is strategically beneficial to appear cooperative (Studies 4–6). Together, our findings contribute to a better understanding of the conditions under which the reputational costs of conspicuous consumption outweigh its benefits, helping integrate theoretical perspectives on strategic interpersonal dynamics, cooperation, and status signaling.

From the General Discussion

Implications

The high demand for luxury goods is typically explained by the social advantages of status signaling (Veblen, 1899). We do not dispute that status signaling is beneficial in many contexts. Indeed, we find that status signaling helps a person gain acceptance into a group that is seeking competitive members (see Supplemental Study 1). However, our research suggests a more nuanced view regarding the social effects of status signaling. Specifically, the findings caution against using this strategy indiscriminately. Individuals should consider how important it is for them to appear prosocial, and strategically choose modesty when the goal to achieve cooperation is more important than other social goals (e.g., to appear wealthy or successful).

These strategic concerns are particularly important in the era of social media, where people can easily broadcast their consumption choices to large audiences. Many people show off their status through posts on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook (e.g., Sekhon et al., 2015). Such posts may be beneficial for communicating one’s wealth and status, but as we have shown, they can also have negative effects. A boastful post could wind up on social media accounts such as “Rich Kids of the Internet,” which highlights extreme acts of status signaling and has over 350,000 followers and countless angry comments (Hoffower, 2020). Celebrities and other public figures also risk their reputations when they post about their status. For instance, when Louise Linton, wife of the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, posted a photo of herself from an official government visit with many luxury-branded hashtags, she was vilified on social

media and in the press (Calfas, 2017).