Kubzansky, L.D., Epel, E.S. & Davidson, R.J.

Nat Hum Behav (2023).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01717-3

Standfirst:

Hopelessness and despair threaten health and longevity. We urgently need strategies to counteract these effects and improve population health. Prosociality contributes to better mental and physical health for individuals, and for the communities in which they live. We propose that prosociality should be a public health priority.

Comment:

The COVID-19 pandemic produced high levels of stress, loneliness, and mental health problems, magnifying global trends in health disparities.1 Hopelessness and despair are growing problems particularly in the U.S. The sharp increase in rates of poor mental health is problematic in its own right, but poor mental health also contributes to greater morbidity and mortality. Without action, we will see steep declines in global population health and related costs to society. An approach that is “more of the same” is insufficient to stem the cascading effects of emotional ill-being. Something new is desperately needed.

To this point, recent work called on the discipline of psychiatry to contribute more meaningfully to the deaths of despair framework (i.e., conceptualizing rises in suicide, drug poisoning and alcoholic liver disease as due to misery of difficult social and economic circumstances).2 Recognizing that simply expanding mental health services cannot address the problem, the authors noted the importance of population-level prevention and targeting macro-level causes for intervention. This requires identifying upstream factors causally related to these deaths. However, factors explaining population health trends are poorly delineated and focus on risks and deficits (e.g., adverse childhood experiences, unemployment). A ‘deficit-based’ approach has limits as the absence of a risk factor does not inevitably indicate presence of a protective asset; we also need an ‘assetbased’ approach to understanding more comprehensively the forces that shape good health and buffer harmful effects of stress and adversity.

My take:

Prosociality refers to positive behaviors and beliefs that benefit others. It is a broad concept that encompasses many different qualities, such as altruism, trust, reciprocity, compassion, and empathy.

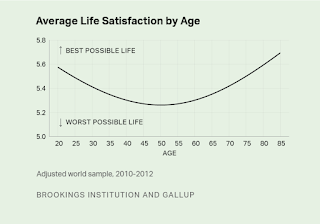

Research has shown that prosociality has a number of benefits for both individuals and communities. For individuals, prosociality can lead to improved mental and physical health, greater life satisfaction, and stronger social relationships. For communities, prosociality can lead to increased trust and cooperation, reduced crime rates, and improved overall well-being.

The authors of the article argue that prosociality should be a public health priority. They point out that prosociality can help to address a number of major public health challenges, such as loneliness, social isolation, and mental illness. They also argue that prosociality can help to build stronger communities and create a more just and equitable society.