Amitha Kalaichandran

Scientific American

Originally posted 5 May 21

Here are two excerpts:

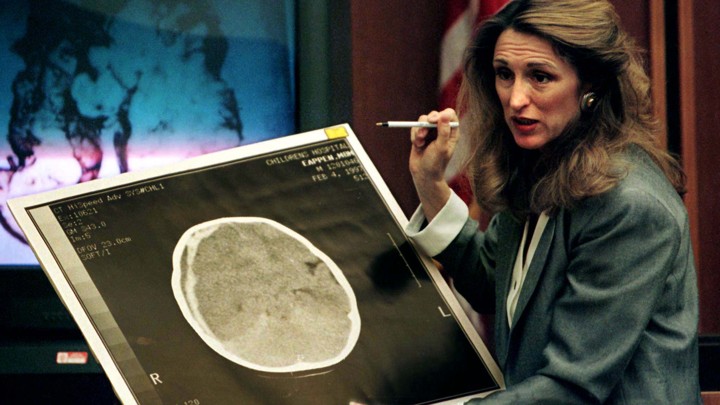

The second issue is that the standard used by the courts to assess whether an expert witness’s scientific testimony can be included differs by state. Several states (including Minnesota) use the Frye Rule, established in 1923, which asks whether the expert’s assessment is generally accepted by the scientific community that specializes in this narrow field of expertise. Federally, and in several other states, the Daubert Standard of 1993 is used, which dictates the expert show their scientific reasoning (so the determination of validity is left to the courts), though acceptance within the scientific community is still a factor. Each standard has its drawbacks. For instance, in Frye, the expert’s community could be narrowly drawn by the legal team in a way that helps bolster the expert’s outdated or rare perspective, and the Daubert standard presumes that the judge and jury have an understanding of the science in order to independently assess scientific validity. Some states also strictly apply the standard, whereas others are more flexible. (The Canadian approach is derived from the case R v. Mohan, which states the expert be qualified and their testimony be relevant, but the test for “reliability” is left to the courts).

Third, when it comes to assessments of cause of death specifically, understanding the distinction between necessary and sufficient is important. Juries can have a hard time teasing out the difference. In the Chauvin trial, the medical expert witnesses testifying on behalf of the prosecution were aligned in their assessment of what killed Floyd: the sustained pressure of the officer’s knee on Floyd’s neck (note that asphyxia is a common cause of cardiac arrest). However, David Fowler, the medical expert witness for the defense, suggested the asphyxia was secondary to heart disease and drug intoxication as meaningful contributors to his death.

(cut)

Another improvement could involve ensuring that courts institute a more stringent application and selection process, in which medical expert witnesses would be required to demonstrate their clinical and research competence related to the specific issues in a case, and where their abilities are recognized by their professional group. For example, the American College of Cardiology could endorse a cardiologist as a leader in a relevant subspecialty—a similar approach has been suggested as a way to reform medical expert witness testimony by emergency physicians. One drawback, according to Faigman, is that courts would be unlikely to fully abdicate their role in evaluating expertise.